The Neuroptera, also known as Planipennia, is one of the oldest insect orders with complete metamorphosis habitat. The Neuroptera or the net-winged insects includes – Mantidflies, lacewings and ant-lions and relatively ranging upto 6000 species. They are grouped together with Megaloptera and Raphidioptera under the superfamily Neuropterida (Planipennia) and distributed among 17 families, the order is relatively small. It includes the green and brown lacewings, antlions, owlflies, dustywings, mantidflies, and allies. Its members occupy a wide variety of habitats and display an array of life styles. Because of their lacey and colorful wings, delicate bodies, and fascinating biology, neuropteran adults attract the attention of both biologists and laypersons.

The name “Neuroptera”—from the Greek words “neuron” meaning “sinew, tendon” and “pteron” meaning “wing”—refers to the netlike arrangement of veins and cross veins in the wings. The term comes from an old usage of the word “nervation”, meaning “strengthening by sinews”.Neuroptera are a group of insects those have 2 pairs of membranous cross veined wings (numerous veins) i.e. four in number. Therefore, they are also known as net-winged insects. They have similar sizes wings with a complex net-like pattern.Neuropterans are rather very fragile insects with distinguishing characteristics. The adult Neuroptera have chewing mouthparts well-developed, but the larval mouthparths are well equipped with piercing and sucking jobs. They undergo complete metamorphosis, and are holo-metabolous in nature.

Green lacewings are insects in the large family Chrysopidae of the order Neuroptera. There are about 85 genera and (differing between sources) 1,300–2,000 species in this widespread group. Members of the genera Chrysopa and Chrysoperla are very common in North America and Europe. Literature suggests that Chrysopa and Chrysoperla are of same species level, however there are speculations about the relativity of these two. Since they are the most familiar neuropterans to many people, they are often simply called "lacewings".

Hemerobiidae is a family of Neuropteran insects commonly known as brown lacewings, comprising about 500 species in 28 genera. Most are yellow to dark brown, but some species are green. They are small; most have forewings 4–10 mm long (some up to 18 mm). These insects differ from the somewhat similar Chrysopidae (green lacewings) not only by the usual coloring but also by the wing venation: Some genera eg. are, Hemerobius, Micromus,Notiobiella, Sympherobius, Wesmaelius

Dilaridae is a family of pleasing lacewings in the order Neuroptera. They were formerly placed in the superfamily Hemerobioidea. But it seems that the Dilaridae are a rather basal member of the Mantispoidea, which includes among others the mantidflies (Mantispidae), whose peculiar apomorphies belie that their relationship to the pleasing lacewings is apparently not at all distant. There are about 9 genera and at least 100 described species in Dilaridae.

The dustywings, Coniopterygidae, are a family of Pterygota (winged insects) of the net-winged insect order (Neuroptera). About 460 living species are known. These tiny insects can usually be determined to genus with a hand lens according to their wing venation, but to distinguish species, examination of the genitals by microscope is usually necessary. A distinguishing feature is that like many other Neuroptera, dustywings carry their wings nearly side-by-side when at rest. They are unique among the living net-winged insects,dustywings do not actually have the "net-winged" venation.

Neuroterans are soft-bodied insects which exhibits some generalized distinguishing features, such as, they have lateral compound eyes, they may or may not have ocelli,except for one family (Osmylidae) whose adults lack ocelli.They lack, however, some other features like most endopterygote insects possess. They have two pairs of usually similar wings which are of same size and shape having distinct unique venation pattern. They may also have some specialized sense organs in their wings, or bristles or some other structures that helps them in connecting the wings during flight. They have three pairs of thoracic legs, each ending in two claws, the abdomen often has adhesive discs on the last two segments.

Neuropteran adults are characterized by the wings, thatare held roof-like over the body while the insect is at rest. Branches of the veins are generally bifurcated at the wing margins. The larvae are specialized predators and they have strong, elongated mandibles useful for pircing and sucking. Adults also have large powerful mandible on their mouthparts useful for chewing and multiarticulate antennae that are usually filiform (threadlike) or moniliform (with bead-like segments). The mesothorax and metathorax are similar in structure, and the cylindrical abdomen lacks cerci.

Neuropteran larvae differ markedly from adults. Larval mandibles and maxillae are usually elongate, slender, and modified for sucking; maxillary palpi are absent. The larval thorax bears walking legs, and the one-segmented tarsus usually ends in two claws that function in locomotion. The terminal adhesive disks of the abdomen also aid locomotion. Like the adult, the larva lacks abdominal cerci.

Neuropteran larvae spin silken cocoons within which they metamorphose. Pupae are decticous; that is, they have strong mandibles that are used to cut open the cocoon. After exiting from the cocoon, the exarate pupae are capable of limited locomotion before they molt to the adult stage; their legs and unexpanded wings are free from the body, and the abdomen is moveable.

Most Neuroptera studies have revealed XX/XY sex determination. However, their sex chromosomes may display an unusual type of pairing (“distance pairing”),

in which the chromosomes do not align to form bivalents during meiosis; rather, they are pulled from within the spindle to stabilized positions at the poles. This form of meio-sis and other cytological features are shared with Raphidioptera. In many neuropteran taxa, meiosis occurs early in development, for example, during the last instar or the pupal stage. In these taxa, adult males have degenerate testes, and mature sperm bundles are stored within the seminal vesicles.

The fossil record of the Neuroptera is fragmentary, ancient (extinct) neuropterans have been traced back reliably to the Late Permian of Eurasia. The affinities of these archaic forms to modern taxa are undetermined; they seem to be a stem group. Other early neuropteran fossils appear in the mid-Mesozoic, some of which are assigned to the extinct family Permithonidae, have a primitive wing structure and their affinities with modern neuropterans are unknown.

The largest recorded neuropteran, a psychopsid-like lacewing (in the family Kalligrammatidae) with a wingspan of 24 cm and large conspicuous ”eyespots” on the wings, existed in the Jurassic. Fossils from the Jurassic are also known for extant families from both suborders (Myrmeleontiformia: psychopsids, nymphids; Hemerobiiformia: polystoechotids, osmylids, chrysopids, hemerobiids, and coniopterygids). Cretaceous amber includes specimens from an array of modern families, including Berothidae, Mantispidae, and Osmylidae, among others, and the diverse Neuroptera found within Baltic amber (Eocene) can be placed within modern families.

Worldwide, the order Neuroptera is distributed thoroughly, except for Antarctica. Europe, North America, and Asia have rich neuropteran faunae as do southern Africa, South America, and Australia. Australia may have the broadest diversity; it lacks representatives from only two families (Dilaridae and Polystoechotidae) and most of the presumed archaic families are represented there (e.g., Nevrorthidae, Sisyridae, Ithonidae). In contrast, New Zealand and the South Pacific islands have only meagre neuropteran faunae. Remarkably, Hawaii appears unique in being the only island group to have evolved complexes of endemic species (Hemerobiidae and Chrysopidae).

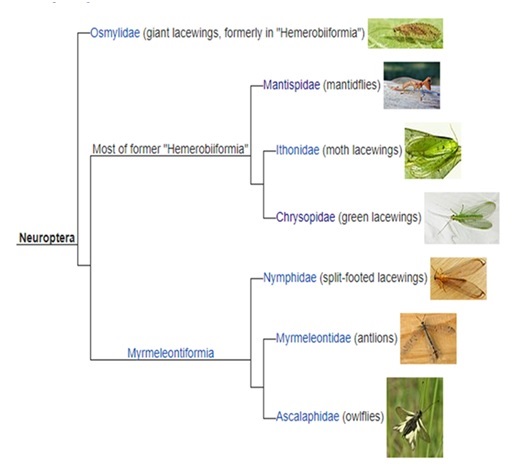

From the understanding of the phylogeny of neuropteran species, it has been found that Megaloptera and Raphidioptera are not grouped with neuroptera strictly. Moreover, Mantispidae and Myrmeleontidae, were confirmed as the closely related groups by cladistics analysis. Though, there are many unsolved issues in grouping the major lineages of neuroptera. The evolutionary context of neuropteran phylogeny has been explored using mitochondrial DNA information, which shows that Hemerobiiformia remains paraphyletic group and Myrmeleontiformia as the monophyletic one suggesting the above cladogram.

However, recent phylogenetic studies have examined the relationships among the three neuropteridan orders; these studies used comparative data from male and female genital structures, larval cryptonephry (fusion of Malphigian tubules to the hindgut), larval head and mouth-part structure, and the molecular structure of several nuclear and mito-chondrial genes. Although not without limitations, the preponderance of current evidence indicates a dichotomy between Raphidioptera and (Megaloptera + Neuroptera) and a relatively well-supported sister relationship between Megaloptera and Neuroptera.

Upon consideration with other orders, the three orders, Megaloptera (dobsonflies, alderflies), Raphidioptera (snakeflies), and Neuroptera, (Neuroptera sensustricto, Planipennia) (lacewings, antlions, dustywings, and allies) form the superorder Neuropterida. Because of its ancient fossil record, the generalized body structure of its larvae and adults, and its exarate pupae, Neuropterida is considered to be among the most primitive taxa within the Holometabola (insects with complete metamorphosis, Endopterygota). Significant morphological and molecular evidence indicates that this superorder is a monophyletic grouping and in a sister relationship with the Coleoptera.

A number of synapomorphic (shared, relatively derived or specialized) characteristics distinguish the Neuroptera as a mono-phyletic order that is separate from Megaloptera and Raphidioptera. Notably, most of these distinguishing features occur in the larvae. For example, megalopteran and raphidiopteran larvae have biting-chewing mouthparts, the mouth opens anteriorly, and the cervix has a single, unarticulated, ribbon-like sclerite. In contrast, the mouth-parts of neuropteran larvae are suctorial and consist of elongate and pointed mandibles and maxillae whose adjacent grooved surfaces form a feeding tube. The mouth, instead of opening anteriorly, connects to the feeding tubes at the sides of the head, and the larva has an articulated, neck-like cervix.

Other larval characteristics distinguish Neuropterans from the other two neuropteridan orders. Neuropteran larvae do not have contiguous intestinal tracts. Rather, the midgut and hindgut remain separate until pupation. As the larvae feed, waste accumulates in the midgut. Only after metamorphosis, during which the midgut and hindgut become connected, do the newly emerged adults expel the feces as a meconial pellet. Neuropteran larvae use the hindgut and associated structures (Malphigian tubules) to produce silken cocoons in which the larvae metamorphose to exarate, decticous pupae. In contrast, megalopteran and raphidiopteran larvae have contiguous intestines, and they do not form cocoons or spin silk; rather, they metamorphose within earthen chambers or wooden cells. Like the Neuroptera, their pupae are exarate and decticous.

The order Neuroptera encompasses 17 families that currently fall into 3 suborders: Nevrorthiformia, Myrmeleontiformia, and Hemerobiiformia. Two of the three suborders, Nevrorthiformia and Myrmeleontiformia, are well supported by morphological and molecular data, and current evidence indicates that an aquatic larval life style was the primitive neuropteran condition. However, the data are contradictory regarding the phylogenetic history of the two hemerobiiform families with aquatic/ semiaquatic larvae—the Sisyridae and Osmylidae. Current molecular evidence can be interpreted as consistent with the retention of a primitive aquatic state in these two families, whereas morphological data from the larvae are consistent with the secondary acquisition of aquatic/semiaquatic life styles.

Neuropteran larvae are much less noticeable than adults and have received much less attention. Unlike the adults, which may or may not take prey, almost all neuropteran larvae are predacious. Several families (primarily Chrysopidae, Hemerobiidae, and Coniopterygidae) are useful in the natural, biological, and integrated cntrol of many economically significant insect pests. But, despite their actual and potential importance, they have received less emphasis than other groups, such as the predacious lady beetles.The immature lacewings are generally predaceous in nature. The immature and the adult Neuropterans are also known as Aphid-lions and they generally feed upon aphids and hence are beneficial and regarded as allies of man. They protect the crop from pest-insects. Adult green lacewings are found throughout the year and the immature ones are often called ‘doodlebugs’, they forms pits and digs in dusty dry soil.

Osmylidae is a family of ~160 species in eight poorly defined subfamilies. Their systematics needs considerable reassessment. Osmylids are slender, moderate-sized lacewings (forewing length 15-30mm), with broad pigmented wings. The family is distributed over much of the Old World; five subfamilies occur in Australia and two in South America. Osmylids have not been found in North America. Knowledge of osmylid biology is sparse. Elongate, knobbed, unstalked eggs are laid with their sides attached to foliage. Larvae live under stones or at the water-l and interface near streams or under the loose bark of trees. Osmylid larvae have long slender stylets like those found in sisyrids (and berothids) but unlike sisyrids, they lack gills and breathe through thoracic and abdominal spiracles.

With ~400 species, Mantispidae is the largest family in the dilarid lineage (Dilaridae, Berothidae, Mantispidae). These moderate to large-sized lacewings (forewing length 5-30 mm) are recognized by raptorial forelegs that resemble those of mantids. Their simple, sub-equal wings are narrow and elongate, and they have a distinct ptero-stigma and chrysopid-like venation. Larvae are similar to those of the Berothidae in that they are hypermetamorphic; however, in the case of the mantispids the first instars are campodeiform and the second and third instars are grub-like. The mantispids differ from the Rhachiberothinae in their wing venation, terminalia, and larval characteristics, but they are of similar body-size and also have raptorial forelegs.

The family contains four, apparently monophyletic subfamilies: Symphrasinae, Drepanicinae, Calomantispinae, and Mantispinae. Symphrasinae encompasses a large, diverse assemblage of species that occur from South America through southern North America. Drepanicinae is a smaller subfamily that occurs in restricted areas within South America and mainland Australia.

Calomantispinae, another small subfamily, also has a disjunct distribution: eastern Australia (including Tasmania), and southern North America. Finally, the large subfamily Mantispinae ranges between 50°N and 45°S throughout much of the world. The biology and immatures of Drepanicinae and Calomantispinae remain largely unknown, whereas those of several genera in Symphrasinae and Mantispinae have been studied.

Larvae in the subfamily Mantispinae usually inhabit the egg sacs of spiders where they feed upon the contents, although some may be subterranean predators or possibly generalist predators. Numerous (200-2000) stalked eggs are laid randomly (and sometimes in clusters) on leaves and other substrates. The newly hatched campodeiform larvae find their hosts (spider eggs) via one of two methods. Either, they actively seek a previously constructed spider egg sac that they enter through direct penetration, or they climb onto a female spider and enter the egg sac during construction. Those that board spiders can feed on the hemolymph of their host, but they do not molt until they enter an egg sac. If the campodeiform larva attaches to a male spider, it may transfer to a female during copulation. After finding an egg sac, the larva feeds on the contents (predation) and undergoes hypermetamorphosis.

The mature larva spins a cocoon within the spider egg sac, and pupation occurs within the larval skin; thus, to emerge, the mature pupa cuts its way through its larval exoskeleton, the cocoon, and the egg sac. Adults are predacious and they are active during the day or night. Overwintering in some species occurs in the first instar, and there may be one to more generations per year.

Several species within the Symphrasinae have been reared from nests of aculeate Hymenoptera or in the laboratory on larvae or pupae of Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, and Diptera. First instars may find their hosts by attaching to an adult bee or wasp and moving into a cell when the egg is laid. Subsequently, they feed on a single host (parasitism) to which they adhere via a sticky, yellow secretion; they have the typical mantispidhypermetamorphosis.

Adult Climaciella can be highly polymorphic, with each of several morphs mimicking a different species of polistine wasp. The proportion of the different morphs may vary depending on the number and aggressiveness of the various wasp species at each locality. However, the larval habits of the Drepanicinae are unknown; Calomantispine larvae may be generalist predators.

It is a very small family including 32 species in six genera: three from Australia, one from southeastern Asia, and two in the southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central America. Adults are large and moth-like (forewing length 15-30mm); they exhibit a variety of plesiomorphic, but few apomorphic characters. The larvae are subterranean and scarabaeiform: their abdomens are large and swollen, legs are short and fossorial, and the short mandibles curve inward and slightly upward. The maxillae are broad and robust; the mandibles are narrow. Eyes are absent.

Ithonid biology is very little known, however studies states that, unstalked eggs are laid singly in the soil, where their sticky surface accumulates soil and sand particles. The larvae of one species in Australia are associated with the roots of Eucalyptus trees and a North American species occurs near creosote bushes. The specific food sources of these larvae (plant, mycorrhizae or other fungi, or associated herbivores) are not known. In one Australian species, five instars have been demonstrated, an unusual trait among neuropterans, which characteristically have three instars. Larval development may take two or more years; pupation occurs within silken cocoons in the soil.

Apparently, mature larvae undergo diapause; adults emerge synchronously in large numbers, usually following a period of rainfall. Males emerge first and form aggregations that attract females; adults live for only a few days.

Chrysopidae, with its ~1200 recognized species, is one of the two large families of Neuroptera, second only to the Myrmeleontidae. The larvae of many chrysopid species feed on insect and mite pests of agricultural crops or horticultural plantings, and because of their value in biological control, chrysopids are the most frequently studied species of the Neuroptera order.

Adults are medium-sized to large, delicate insects with four subequal wings (forewing length 6-35 mm) and relatively long, filiform antennae. In most species the adults are green with large golden eyes, but some species have black, brown, or reddish adults.

Larvae vary in shape and habits; some are voracious, active, and more-or-less generalist predators, with sleek, fusiform bodies (thus the name ”aphis-lions”). Others are slow-moving, cryptic, trash-carrying predators with bulbous bodies, elaborate tubercles, and long, hooked setae; they are usually associated with specific types of ant-tended prey. Still others live in ant nests where they feed on the inhabitants; they have rotund, bulbous bodies, greatly shortened appendages, and a dense covering of stiff, hooked setae that hold protective trash on the body.

Currently, the Chrysopidae comprises three subfamilies (Nothochrysinae, Apochrysinae, and Chrysopinae); all three are only weakly supported by molecular data and only the first is well defined on the basis of adult and larval characters. Systematic and comparative biological studies are needed to clarify the taxonomy and phylo-genetic relationships of the chrysopid taxa and also to facilitate their use in biological control. From the study of the wide range of morphological and behavioral variation among chrysopid larvae, it is clear that inclusion of all life stages is crucial for advancing the systematics of the family. Recent studies of previously unknown larvae have led to changes in the tribal assignments and the recognition of new Neotropical genera. However, except for the European and Japanese faunae where larvae of approximately 80% of the species are described, the world’s chrys-opid larvae are poorly known.

The Nothochrysinae includes only nine extant genera; it is believed to be the basal chrysopid lineage, but molecular data have not confirmed this opinion. Defining characteristics occur in the adult and larval stages; however, larvae from very few genera are known.

Apochrysinae may be monophyletic, but more supporting data are needed. The larvae of one apochrysine species have been described, but distinguishing subfamilial traits were not apparent. The subfamily contains the largest and visually most spectacular green lacewings; its ~13 genera are based largely on somewhat variable characters in wing venation. Biological studies are needed.

The large subfamily Chrysopinae encompasses over 97% of the known chrysopid species; it includes ~60 genera distributed among four tribes, at least two of which are poorly defined and probably not monophyletic. The tribe Chrysopini is the largest and least well known; it contains almost all of the lacewings of economic importance.

As a cosmopolitan group, the Chrysopidae subfamilies are widely distributed. However, many of the genera have limited geographic distributions. For example, among the Apochrysinae, two genera occur only in Africa, four in the Neotropics, six in the Oriental region or Australia, and one in the eastern Palearctic. Most genera of Nothochrysinae are endemic to small geographic ranges; many species are known solely from a very few specimens. The genera within Chrysopinae range from cosmopolitan to narrowly endemic.

Typically, chrysopid eggs are laid at the end of long stalks, either singly, in groups, or in clusters with the stalks loosely or tightly intertwined. The egg stalks can be naked or they may bear oily droplets; the droplets contain nutrients or defensive substances that protect the egg or the newly hatched larva from natural enemies.Larvae of some chrysopid species have fairly large prey ranges; they may feed on homopterans, lepidopteran eggs or larvae, and a variety of soft-bodied arthropods. But, contrary to popular lore, some species have evolved a very strong association with a particular type of prey.

In Chrysopa, prey specialization can be restricted to a single species of prey and is based on a suite of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including maternal oviposition behavior, egg size, larval morphology and behavior, phenotypic plasticity in life-history traits, responses to natural enemies that are associated with specific prey, and phenology.

Studies also indicate that prey association, such as that in Chrysopa, and also habitat association, as shown in Chrysoperla, can evolve in a manner that is very similar to the evolution of host specificity in phytophagous insects; there is good evidence that both can be involved in speciation.

Adults of most chrysopid genera feed on honeydew and pollen; in these lacewings, the dorsal crop diverticulum has numerous tracheae and is filled with symbiotic yeast. These symbiotes provide essential nutrients that are deficient in the diet. Adults in a few genera are predacious. In some species, adults emit foul-smelling defensive odors when they are disturbed.

Some chrysopid species are multivoltine, others are univoltine; most enter diapause and undergo dormancy (hibernation, aestivation) during unfavorable (e.g., cold, hot, or dry) seasons. The dia-pausing stage (free-living larva, prepupa, or adult) varies among lacewings and is a characteristic of the genus. Some chrysopids that diapause as adults undergo seasonal color changes that appear to reflect the background color of their habitat during the unfavorable season. Although lacewings are not considered especially strong flyers, they can move considerable distances with the wind. In species that diapause as adults, there is a seasonal pattern to movement between habitats. Photoperiod often provides very important cues for timing lacewing dormancy and seasonal movement; temperature, moisture, and food can also be significant factors. The genetic basis for lacewing responses to seasonal cues has been demonstrated; some exhibit geographical variability and epistasis.

Chrysopine lacewings have two modes of hearing. The “ear” (tympanal organ) is at the base of the radial vein in each forewing. It is the smallest tympanal organ known, and it receives the ultrasonic signals of insectivorous bats. Ultrasonic signals at low rates 50 pulses per second) cause the lacewing to cease flight and to fall. As the bat continues to approach, its signal increases in frequency; the high-frequency signal causes the lacewing to flip its wings open quickly and fly, thus aiding its escape. The second type of hearing, the perception of low-frequency, substrate-borne sounds that are emitted during courtship, is accomplished through scolopidial organs in the legs. Such sounds are an integral part of courtship in Chrysoperla species; variation in the production and perception of these sounds may have a role in speciation.

The endemic complex of green lacewings on the Hawaiian Islands, belonging to the genus Anomalochrysa, has evolved several unique characteristics and exhibits an extraordinary range of variation in morphology and behavior. For example, unlike any other known chrysopids, Anomalochrysa females lay sessile (unstalked) eggs, either singly or in batches. Larval body shapes range from fusiform with greatly reduced lateral tubercles and few, short setae, to flattened with well developed lateral tubercles and numerous, long, robust setae. In continental lineages, such broad variation is found only among genera. In some species, adults or larvae are very bright and colorful; in others they are dull or resemble bird feces. Males and females may produce conspicuously loud clicking sounds during courtship and mating; how these sounds are produced and perceived is unknown.

Some species in the genus Chrysoperla are mass-reared for release in the biological control of agricultural and horticultural pests. Among those in North America are Chrysoperla carnea and Chrysoperla rufilabris. These species possess characteristics that are advantageous for mass-rearing. For example, adults do not require prey, but will reproduce when fed artificial diets; they can be stored for long periods without significant loss of reproductive potential; and larvae can develop when fed artificial or factitious prey. Larvae of Ceraeochrysa species, which are trash-carriers, share many of the above traits that subserve mass production. They have the added advantage of being camouflaged and thus protected from their own natural enemies, for example, ants. The role of lacewings, thus in pest management, whether naturally occurring or augmentative, is far from fully exploited.

This small neuropteran family is restricted to the Australian region (Australia, New Guinea, and nearby islands); and it contains 35 species in seven genera. Currently the Nymphidae includes two well-defined lineages, the subfamilies Myiodactylinae and Nymphinae. Nymphid adults are large (forewing length 18 to >40mm). They may resemble myrmeleontids, but they have long, slender antennae.

Nymphid eggs are laid on slender, filamentous stalks. In Myiodactylinae, the stalks are either pendant or looped, so that the egg contacts the substrate. In Nymphinae, the eggs are arranged in intricate patterns. In both subfamilies, the stalk may be coated with beads of liquid that may serve nutritional and/or defensive functions. Myiodactyline larvae are very flat, and the margins of their bodies have long scoli, they are green and arboreal, and they rest on the surface of leaves with the jaws at an angle of —180°.

Nymphine larvaelive in litter or on the bark of trees where they are camouflaged by the debris they carry or by the markings on the body.

Cocoons probably are spun in sand. Adults of one species form large aggregations, but the function (e.g., mating, defense) of the aggregations is not known. Some species occur in association with acacias. Adults produce an odor from eversible abdominal glands and copulation involves enlarged and elaborate male terminalia that presumably have a grasping function.

With about 2100 species in 300 genera, the antlions constitute the largest neuropteran family. Members of this family have intrigued naturalists from the earliest times such as W. M. Wheeler, who provided imaginative accounts in his 1930 topic, Demons of the Dust. Most people know antlions because the larvae of some species have pit-building habits. Myrmeleontid larvae do not feed exclusively on ants and most do not construct pits. Adults are slender bodied and medium to large-sized (forewing length10 – 70 mm).

Four subfamilies of Myrmeleontidae are generally recognized: Myrmeleoninae, Palparinae, Acanthaclisinae, and Stilbopteryginae (formerly a separate family, Stilbopterygidae). Larval morphological and biological characteristics are crucial in the classification of the family, especially at the tribal level but also for many genera. This family has a worldwide distribution, notably in the arid and semiarid areas of subtropical and tropical regions of Africa, Australia, Asia, and the Americas. Myrmeleontids inhabit open woodlands, scrub grasslands, and dry sandy areas. Efforts have been made in South Africa to assess the taxonomic richness of the large fauna and to help conserve it.

Myrmeleontid eggs are unstalked and relatively large; they are laid singly in open areas or tree holes, under bushes, in caves, under rock overhangings, or in areas sheltered by buildings. The eggs are covered with a glandular secretion that facilitates adhesion of sand or soil particles, and they lack an oviruptor.

The larvae of most species appear to be “sit and wait” predators. In most taxa they live beneath the soil surface, on trees, in tree holes, under stones, or in debris. Larvae in a very small number of genera construct pits in sand or soil that entrap prey.

For a few species, the interactions of pit architecture, pit location, prey availability, and larval growth have been studied extensively. The larvae of some myrmeleontid species can travel quickly over the surface of the sand; others have slow, creeping movements or fast backward movements under the sand. These behavioral patterns are aided by the forward-directed terminal segments (fused tibia-tarsus) of the hindlegs, and they have led to the common name, “doodlebugs.” Ingestion is accomplished by the injection of digestive enzymes from the midgut into the prey, followed, after several minutes, by sucking. The regurgitated gastric juice is not mixed with the contents of the crop or the midgut.

Whereas, it appears to be extruded from the space between the peritrophic membrane and the epithelium of the midgut, then contractions of the crop’s muscular system transport the fluid forward through a fold in the wall of the crop.

Larvae has to pass through three instars. In some species, larval development can be protracted over several years depending upon the availability of prey; overwintering occurs in the larval stage. Univoltine or semivoltine life cycles are influenced by photoperiodic and thermal responses during early and late larval stages; pupal size may also be important in determining the number of generations per year. Larvae generally spin a single-walled cocoon; a double-walled cocoon occurs in one unusual South American species.

Adults are largely nocturnal and presumed predacious. Their flight resembles that of damselflies. Sexual communication involves the extrusion of “hair pencils” and abdominal glands or sacs on the male (analogous to those found in lepidopteran males), as well as the release of volatile substances from thoracic glands in both males and females.

The owlflies constitute a medium-sized neuropteran family of 430 species assigned to 65 genera. Adults are distinguished from myrmeleontid adults by their long, clubbed antennae. There are three subfamilies: one with bisected eyes (Ascalaphinae) and two with entire eyes: Haplogleniinae and Albardiinae. The subfamily Albardiinae consists of a single, very unusual, large-bodied Brazilian species.

The two major subfamilies (Ascalaphinae and Haplogleniinae) are widely distributed in the warm regions of the world, but the Haplogleniinae only occurs in Australia. Ascalaphids inhabit grasslands and warm dry woodlands. Most species are nocturnal or crepuscular, but some Eurasian species are diurnal and have pigmented wings that resemble those of butterflies. Adults are relatively large (forewing length 15-60 mm).

Clusters of 20 to 75 large, unstalked eggs are laid on twigs in spirals or rows. Individual eggs are reported to have two micropyles, but lack an oviruptor. Females of many species place small, modified eggs (repagula) on or around egg batches, and these repagula have defensive and nutritional functions. They serve to divert or repel predators and/or provide food for newly hatched larvae. The two major subfamilies in the New World possess this habit, but it is absent from Old World and Australian ascalaphids.

Newly hatched larvae often remain together near the egg cluster for a week or more before dispersing. Larvae are either terrestrial (in the soil or litter) or arboreal (on leaves or tree trunks), and most appear to be “sit and wait”. Characterized by holding their jaws open at very wide angles, some New World species resemble nymphids in being able to open their jaws beyond 270°. Larvae can take relatively large prey, and when a larva contacts prey, its jaws can close very rapidly. Considerable evidence shows that the larvae paralyze their prey with toxins from the midgut, not from glands. As with other myrmeleontiform larvae, there are three instars.

Larvae of some species that live in the soil or sand, camouflage themselves with sand grains or debris. Such behavior shares features with the “camouflaging” behavior of chrysopid larvae, but ascalaphid larvae use their flexible foretarsi, rather than the jaws, to place material on their dorsa. A thick mat of tangled threads anchors the debris to the dorsal surface. Second and third instars resist starvation well, and development may extend to one or two years. Because ascalaphid adults occur at specific times of the year, diapause probably intervenes in some larval stages. Photoperiod or other factors may serve to regulate the occurrence of diapause, but the responses and mechanisms have not been studied. Pupation occurs within silken cocoons that are spun on the ground or on trees, also sometimes they incorporate sand or debris.

Adults remain motionless in a characteristic head-downward position for most of the day when flight is restricted to a relatively short period around dusk and is preceded by about 10 minutes of muscle-warming via wing vibration. Compared to other neuropterans, ascalaphids have strong and agile flight, similar to that of dragonflies. Adults feed on large numbers of flying insects (e.g., caddisfly adults), prey capture and mating occur on the wing.

Apart from Chrysopidae, there are three more Neuroptera families of economic importance –

Hemerobiidae constitutes a cosmopolitan clade that is relatively well known and easily recognized. It is the third largest neurop-teran family, with ~550 species. Adults are generally small (forewing length 3-18 mm), brown, and inconspicuous. The ~27 extant genera of hemerobiids fall into ten reasonably well-defined subfamilies. The Carobiinae and Psychobiellinae each consist of one genus that is restricted to the Australian region. Each of the Hemerobiinae, Sympherobiinae, Notiobiellinae, and Microminae include three to five genera; all four of these subfamilies are cosmopolitan, but some of the small genera that they encompass have very restricted distributions. The Drepanacrinae and Drepanepteryginae each contain three genera with restricted distributions, and the Megalominae comprises one genus with broad distribution. The most recently described subfamily, Adelphohemerobiinae, consists of a single genus known only from South America.

Larval morphology may offer a rich suite of traits for phyloge-netic analysis; however, the larvae of only nine genera (from 7 of the 10 subfamilies) have been described. There are three instars. In the first instar, body setation is sparse, and trumpet-shaped empodia are present between the tarsal claws. Second and third instars are similar to each other except in size, however, they may have numerous short setae, and their empodia are short.

Mainly because the systematics of the family was neglected until recently, the life cycles of relatively few hemerobiid genera are known, and the groups that have been studied occur largely in the Northern Hemisphere. In general, hemerobiid eggs are sessile (unstalked) and laid singly or in clusters. Hatching is accomplished by means of an oviruptor.

Larvae prey upon a variety of small, soft-bodied arthropods and eggs. Little is known about the range of larval diet or its specificity, but some species have a strong association with a particular type of plant or habitat, and it is likely that some of these are also specific in their diets. Pupation occurs within thinly s pun cocoons. Pupae have a peculiar set of hooks on the dorsum of the abdomen; their function is unknown. Most species seem to be predacious in the adult stage, but there are records of extensive honeydew feeding by adults. Life cycles range from univoltine to multivoltine, but for most taxa the overwintering stage is unknown.

Flightlessness has evolved several times in the Hemerobiidae; it is largely confined to species that occur on islands or are restricted to isolated mountains. In flightless forms, the hindwings are greatly reduced or absent, or the forewings are hardened or fused. Modifications associated with flightlessness are probably most extreme in the endemic Hawaiian Micromus. Pronounced sculpturing of the wings also occurs in winged (and flighted) endemic Hawaiian Micromus species. Many species of Hemerobiidae may be important natural enemies of arthropod pests on agricultural and horticultural crops or in forests. Hemerobiids often are active at relatively low temperatures; thus they can be useful as biological control agents in temperate regions early in the season when other natural enemies remain inactive.

Because of their small size and cryptic nature, coniopterygids are generally overlooked and thus considered rare. However, with 450 species, the Coniopterygidae constitutes a relatively large family and is one of the best-known systematically. Although they clearly belong within the Neuroptera, coniopterygids differ in a number of ways from other neuropteran families. Previously, they were considered the sole family of a separate primitive suborder (superfamily), the Coniopterygoidea. However, a recent cladistic analysis provides some evidence that the Coniopterygidae and Sisyridae may form a derived sister group within the Hemerobiiformia.

The Coniopterygidae is generally a very homogeneous family characterized by very small adults (forewing length 2-5 mm) with bodies covered by white waxy (“dusty”) secretions. The secretions originate from hypodermal wax glands on the sternites and tergites of the abdomen and are spread over the body by the hindlegs. Other than in the coniopterygids, such glands are only found in the homopteransAleurodina and Coccina. This similarity represents a remarkable example of convergent evolution especially because coni-opterygids frequently are associated with these waxy homopterans.

Currently, the Coniopterygidae contains three well-defined, probably monophyletic subfamilies: Coniopteryginae, Aleuropteryginae, and Brucheiserinae. Both the Coniopteryginae and the Aleurop-teryginae are large groups with cosmopolitan distributions.

The Brucheiserinae differs from the other two subfamilies in having highly unusual reticulate wing venation. Brucheiserinae is known only from the neotropics and its larvae are not described. Some authors have considered it a separate family (Brucheiseridae), but this distinction is probably not justified. In this regard, discovery of the larvae may be very valuable.

The life histories of very few coniopterygid species are known. Both larvae and adults occur on trees and bushes (sometimes on low vegetation). Many species appear to be associated with specific types of vegetation, and this habit may indicate prey specialization. Eggs are unstalked and laid near prey; there are three instars (Fig. 8F).

Adults and larvae prey on small, soft-bodied arthropods (aphids, scales, mites); adults may also feed on honeydew and perhaps pollen. Flat cocoons with double walls are spun on foliage or tree trunks. Adults are usually active at dusk or at night. Life cycles and overwintering stages vary (prepupae within cocoons, free-living second instars) and have not been well studied.

Many species of coniopterygids are considered to be important natural biological control agents but unfortunately, their role has not been evaluated and their potential remains unknown.

This comprises a small family of 50 species which have well-defined affinities with the Berothidae and Mantispidae. It contains two subfamilies: Dilarinae, which is confined to the Old World, and Nallachiinae, which occurs in the New World (with one species known from South Africa). It is one of the few neuropteran families absent from the Australian region.

Adults resemble small, delicate hemerobiids (forewing length 3-16mm in males and 5-22mm in females). But, they are differentiated by ocelli-like tubercles on the head of both sexes (functional ocelli are absent), a long ovipositor in females, and pectinate antennae in males.

Dilarid eggs are elongate and unstalked. Those of Nallachus are laid in association with dead trees. The larvae of Nallachus inhabit the galleries of insects in decaying logs or the area beneath the tightly adhering bark of erect, recently dead trees. Larvae of Dilaridae have been found in the soil, but their biology of larval diet is not known. Development probably takes one year. Larvae may undergo supranumerary molts which means, if undernourished, they may continue to molt as many as 12 times. However, when this happened under laboratory conditions, did not metamorphose successfully.

Several chrysopid species are included among the most important aphidophagous predators. Their efficacy in biological control of aphids, as well as other arthropod pests has been well recognized for more than 250 years (Senior and McEwen, 2001). Due to the larval polyphagous feeding habits, chrysopids are considered to be important natural enemies of several pests besides aphids, such as whiteflies, thrips, lepidopteran pests and mites (Principi and Canard, 1984). In the context of biological control, most attempts have evaluated the efficacy of Chrysoperla carnea sensu lato in augmentation releases in the field or in the greenhouses (Ridgway and McMuphy, 1984; Hagen et al., 1999; Nordlund et al., 2001).

An important issue in the successfull use of chrysopids in biological control is the problematic systematics that still persists in the identification of Chrysoperla species (Tauber et al., 2000). Failures in chrysopid releases may, at least to some extent be explained by importations of wrongly identified species (Senior and McEwen, 2001).

In cases when the use of commercialy available chrysopids such as Chrysoperla carnea (Stephens) or Chrysoperla rufilabris (Burmeister) is problematic, other species could be exploited.

Species of the genera Mallada Navás, Dichochrysa Yang and Ceraeochrysa Adams might be proven efficient candidates for use in biological control (López - Arroyo et al., 1999a, b; Tauber et al., 2000; Daane, 2001). Data on the predation efficacy of other chrysopid species besides Chrysoperla are limited and mainly referred to laboratory conditions.

Research on chrysopid species occurs worldwide and comprises recently an important section in applied entomological research. The International Association for Neuropterology (IAN, www.neuroptera.com) consists a scientific forum that provides the opportunity for communication between researchers interested in the study of Neuropteroidea in general. Many of the IAN members are actively involved in the study of the biology and use of chrysopids in biological control programs. Their work has been well documented and summarized in the Proceedings of International Symposia organized by the Association. Ten Symposia have been held since 1982 and the Proceedings of most of them have been published or are currently in press (Gepp et al., 1984, 1986; Mansell and Aspöck, 1990; Canard et al., 1992, 1996; Panelius, 1998; Sziraki, 2002; Pantaleoni et al., 2005 (2007).

Research on all aspects of the biology of chrysopids and their use in biological control has been comprehensively reviewed since 1984 in two books, the ‘Biology of Chrysopidae’ edited by Canard et al. (1984) and "Lacewings in the Crop Environment" by McEwen et al. (2001). In the present study, the integration of most important factors that could affect and shape the efficacy of chrysopid species in biological control, as well as considerations for further research have been reviewed.

The family Chrysopidae contains about 1200 species that belong in 75 genera and 11 sub- genera. The larvae of all species, as well as the adults of certain species are predaceous and could be important biological control agents of several soft-bodied arthropods, such as aphids, coccids and mites. Due to their important role in biological control programs, the species of the family Chrysopidae are the most well studied among Neuroptera (Brooks and Barnard, 1990).

Chrysopid systematics have been problematic for a long time with a great number of species from different places of the world and different time periods to be wrongly referred to as species of the genus Chrysopa Leach (New, 2001). An important contribution to avert these conflicting and contradictory assumptions was the review of Brooks and Barnard (1990) that identified and presented 1200 species of the family with regard mainly to the morphology of male genitalia. These species have been categorized in three sub-families, namely Nothochrysinae, Apochrysinae and Chrysopinae based on adult morphology (Brooks and Barnard, 1990). The Chrysopinae includes almost 97% of well known chrysopid species and specifically all those species of great economic importance commonly attracted in houses by lights during night (Brooks and Barnard, 1990; De Freitas and Penny, 2001). The species that belong to the genera Dichochrysa, Chrysopa, Ceraeochrysa and Chrysoperla Steinmann are considered to be the most important and abundant biological control agents (Brooks and Barnard, 1990; Albuquerque et al., 2001; Daane, 2001).

Dichochrysa is to date the largest in species number genus of the family Chrysopidae with at least 130 described species that can be found worldwidely but not at the Neotropics (Brooks and Barnard, 1990). According to morphological, biological and phylogenetic studies, many more Dichochrysa species will be discovered in the future in other places of the world (Aspock et al., 1980; Brooks and Barnard, 1990; Dong et al., 2004). Many species formerly described in the genus Mallada by Brooks and Barnard (1990), are now considered to belong to Dichochrysa based on morphological features (Brooks, 1997), although differences in their biology remain to be defined (New, 2001). Furthermore, the genus Anisochrysa Nakahara is considered to be synonym to Mallada (Dong et al., 2004). According to Daane (2001), species that belong to Mallada genus will prove to be efficient biological control agents in the future. Dichochrysa species have been recorded in several field crops such as fruit and nut orchards, vegetables, ornamentals, as well as in forests (Greve, 1984; New, 1984; Semeria, 1984; Zeleny, 1984; Duelli, 2001; Szentkirályi, 2001a, b). Only the trash-carrier larvae are predaceous, whereas the adults feed mainly on pollen and honeydew (New, 2001).

Several species of the family Chrysopidae have been for a long time mistakenly considered to belong to the genus Chrysopa. According to Brooks and Barnard (1990), Chrysopa sensu stricto genus includes approximately 50 species and some sub - species. Both the adults and larvae are predaceous (New, 2001).

The genus Ceraeochrysa includes 46 species and is the dominant genus in the Neotropics (Brooks and Barnard, 1990; Tauber et al., 2000).Ceraeochrysa species are recorded from Canada to Argentina and mainly in the tropics (De Freitas and Penny, 2001). They are commonly found in orchards and several agroecosystems where they are important biological control agents (Lopez-Arroyo et al., 1999a, b; Tauber et al., 2000; Albuquerque et al., 2001).

The genus Chrysoperla includes approximately 36 species that can be found worldwidely (Brooks and Barnard, 1990). Their biology and ecology have been extensively studied and these are the species that are mainly used in biological control programs (Brooks, 1994; New, 2001). However, Chrysoperla systematics are currently problematic, especially for those species of the- carnea group (Brooks, 1994). The adults are not predaceous and feed on honeydew and pollen, whereas larvae are polyphagous predators (New, 2001).

The biology of the most well studied chrysopid species has been reviewed by Canard and Principi (1984), Canard (2001) and Canard and Volkovich (2001).

Chrysopid eggs are oval, white, yellow or green, their size ranges from 0.7 to 2.3 mm and are usually laid on the edge of a silken stalk (with the exception of the species that belong to the genus Anomalochrysa McLachlan which lay unstalked eggs) (Gepp, 1984). The stalk is assumed to play an important defensive or nutritional role for the newly hatched larva and its length is a species specific characteristic that may vary from 2 to 26 mm and be influenced by the mother’s body size, as well as environmental conditions (Tauber et al., 2003). Recently, two silk genes expressed by Mallada signata (Schneider) females were identified and sequenced by Weisman et al. (2009).

Eggs are usually laid by the female singly or in clusters (Duelli, 1984; Gepp, 1984) on the underside or on the top of leaves or shoots where there is plenty of food facilitating its discovery by the young larvae (Duelli, 1984). Embryonic developmental time depends mainly on temperature. For example, C. carnea embryos develop in about 13 days at 15°C and 2.5 days at 35°C, whereas for Chrysoperla externa (Hagen) in 14 and 4 days, at 15.6 and 26.7°C, respectively (Canard and Principi, 1984; Albuquerque et al., 1994).

Chrysopid larvae (three larval instars) can be divided in two groups in respect to their morphology and behavior (Gepp, 1984; Diaz-Aranda et al., 2001; Tauber et al., 2003). In the first group, the debris-carrying larvae or trash-carriers (e.g., larvae of the genera Dichochrysa, Ceraeochrysa, Glenochrysa Esben-Petersen, Leucochrysa McLachlan, Italochrysa Principi), collect with their mouthparts several pieces of plant material, exuviae or dead prey items and place them on their dorsa, thus forming a small ‘packet’ of ‘trash’ that is supposed to protect them from ants and other natural enemies (Eisner et al., 1978). In the second group, the larvae do not carry trash on their dorsa and are naked (e.g., Chrysoperla larvae).

Larval development is mainly influenced by temperature (Canard and Principi, 1984). In most cases, developmental time is shorter in Chrysoperla sp. in relation to Dichochrysa sp. or Nothochrysa McLachlan sp. For example, the larval developmental time for C. externa ranged from 46.5 days at 15.6°C to 12.2 days at 26.7°C (Albuquerque et al., 1994), whereas for Dichochrysa prasina Burmeister ranged from 85 to 19.7 days at 15 and 30°C, respectively (Pappas et al., 2008a). All chrysopid larvae are polyphagous predators with a broad range of prey, such as aphids, coccids, cicadellids, whiteflies, thrips, psyllids, eggs and larvae of Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Diptera or Neuroptera and eriophyid or tetranychid mites (Canard and Principi, 1984; Canard, 2001). Prey location is usually random but there are also cases when it has been mediated to a certain extent by the honeydew produced by the prey (Canard, 2001). There are also chrysopid species that are highly specific to a certain prey species, such as Chrysopa slossonae Banks larvae which are only associated with the wooly alder aphid, Priciphilus tesselatus (Fitsch) (Tauber and Tauber, 1987; Milbrath et al., 1993). Larval prey quantity and quality may have a great influence on preimaginal development, as well as on the reproductive potential of adults (Principi and Canard, 1984; Canard, 2001).

Upon the completion of larval development, the third instar fully grown larva spins a cocoon and remains inside it until adult emergence (Canard and Principi, 1984). Cocoons are usually placed on the plant, inside curled leaves, on the leaves or in the soil (Canard and Volkovich, 2001). The development of the cocoon usually lasts for one or two weeks and depends on several factors, mainly temperature and sex. For example, cocoon development in C. externa was completed in 7.1 days at 24°C, whereas for Chrysopa pallens (Rambur) in 12.7 days at 20°C (Grimal and Canard, 1990; Carvalho et al., 1998).

Most of chrysopid adults are not predaceous and feed on plant derived food, such as nectar and pollen, as well as with insect honeydew (e.g., aphid or coccid honeydew). Pollen grains have been found in relatively high quantities in the digestive trunk of C. carnea and D. prasina adults (Bozsik, 1992, 2000; Villenave et al., 2005). The adults of species of the genera Anomalochrysa, Atlantochrysa Hölzel and Chrysopa are considered to be predaceous (Brooks and Barnard, 1990). Besides several insects, such as aphids, coccids and mites, other food type like pollen grains, fungi spores and yeast have also been identified in the midgut of predaceous chrysopid adults (Principi and Canard, 1984; Bozsik, 1992; Canard, 2001).

To date, published research articles have mainly focused on the effects of several factors on certain biological aspects of chrysopids relative to their use in biological control. A great number of researchers have studied the effects of several abiotic factors, such as temperature (Honek and Kocourek, 1988; Tauber et al., 1987, 2006; Albuquerque et al., 1994; Volkovich and Arapov, 1996; López-Arroyo et al., 1999a; Nakahira et al., 2005; Mantoanelli et al., 2006; Silva et al., 2007; Pappas et al., 2008a, c), photoperiod (Tauber and Tauber, 1972; Hodek and Honek, 1976; Nechols et al., 1987; Canard, 1988, 1990, 1997, 2005; Grimal, 1988; Canard and Grimal, 1988; Chang et al., 1995; Volkovich and Arapov, 1996; Volkovich and Blumental, 1997; Fujiwara and Nomura, 1999; Macedo et al., 2003; Nakahira and Arakawa, 2005), relative humidity (Tauber and Tauber, 1983; Pappas et al., 2008b) or CO2 (Gao et al., 2010) on certain life-history traits and predation capacity of chrysopids.

In Integrated Pest Management (IPM) programs, biological pest control with chrysopids could be efficiently combined with the use of selective pesticides. Vogt et al. (2001) have reviewed the effects of different management practices, such as the use of pesticides and transgenic Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) plants on C. carnea sensu lato. There are many studies focusing on the effects of pesticides commonly used in agriculture on certain life-history traits of chrysopid species (Liu and Chen, 2000; Qi et al., 2001; Carvalho et al., 2002, 2003; Chen and Liu, 2002; Medina et al., 2003; Bueno and Freitas, 2004; Godoy et al., 2004; Ferreira et al., 2006; Silva et al., 2005, 2006; Nadel et al., 2007; Rezaei et al., 2007; Giolo et al., 2009; Mandour, 2009; Schneider et al., 2009) and on pesticide resistance development (Pathan et al., 2008, 2010; Venkatesan et al., 2009), mostly suggesting the relatively broad tolerance of chrysopids to many pesticides. Furthermore, there are several research papers reporting the effects of Bt on the performance of chrysopid species (Hilbeck et al., 1998a, b, 1999; Meier and Hilbeck, 2001; Dutton et al., 2002; Romeis et al., 2004; Pilcher et al., 2005; Rodrigo-Simon et al., 2006; Mellet and Schoeman, 2007; Sharma et al., 2007; Sisterson et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2008; Lawo and Romeis, 2008, Li et al., 2008, 2010; Mason et al., 2008).

With the attempt to evaluate the quality of certain prey species, as well as the predation efficacy of chrysopids, there are a lot of published papers mostly focusing on the performance of larvae and less on adults (Zheng et al., 1993a, b; Legaspi et al., 1994; Giles et al., 2000; Chen and Liu, 2001; Limburg and Rosenheim, 2001; Patt et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2004; Pappas et al., 2007, 2008c, 2009; Cheng et al., 2009, 2010; Huang and Enkegaard, 2010). The efficiency of chrysopids has also been also evaluated in the context of IPM revealing the biotic potential of this group of aphidophagous predators in agricultural practice (Reddy, 2001; Corrales and Campos, 2004; Furlong et al. 2004; Santos et al., 2007; Mirmoayedi and Maniee, 2008, 2009; Turquet et al., 2009).

To date, the mass-rearing of commercially available chrysopids is mainly based on eggs of lepidopteran species of the genera Sitotroga, Ephestia (Anagasta) and Corcyra that have been proved as nutritionally superior and of low cost food to produce, in comparison to other artificial diets tested (Tauber et al., 2000; Riddick, 2009). Until now, any attempts to develop a sufficient and low cost artificial diet that could replace the use of prey species eggs were unsuccessful (Ridgway et al., 1970; Cohen and Smith, 1998).

Although most research projects have been focused on the development of the best food for rearing larvae, mass-rearing of adults has not received much attention (Nordlund et al., 2001). Non predaceous chrysopid adults (e.g., Chrysoperla adults) are usually reared on a proteinaceous liquid diet consisting of a mixture of protein hydrolysate, sucrose and water (Hagen and Tassan, 1970). However, when considering predaceous adults (e.g., Chrysopa adults), their mass-rearing is difficult and very costly (Tauber et al., 2000).

The evaluation of artificial and factitious foods on the performance of several chrysopid species has been the subject of many published research articles. From the mass-rearing of chrysopids perspective, several methods for the production of larvae by offering an artificial diet (Cohen and Smith, 1998; Vasquez et al., 1998; Zaki and Gesraha, 2001; Sattar et al., 2007; Sattar and Abro, 2009) or a factitious food (Singh and Varma, 1989; Pappas et al., 2007, 2008a; Matos and Obrycki, 2006; Sattar and Abro, 2009) have been tested for different chrysopid species. Mass-rearing techniques have been reviewed in extent by Tulisalo (1984), Tauber et al. (2000) and Nordlund et al. (2001).

The automation of mass-rearing systems of Chrysoperla species is still in progress with the aim to save production costs and space (McEwen et al., 1999). Such systems include suitable techniques for maintaining chrysopid adults, automatically feeding larvae and collecting eggs for mass- rearing a large number of larvae (Tauber et al., 2000). The automation of one of more steps in the mass- rearing of Chrysoperla species could result in the reduction of production costs and the enhancement of their commercial availability (Nordlund and Correa, 1995; Nordlund et al., 2001).

The short term storage of eggs and diapausing adults of certain Chrysoperla species could be achieved at low temperatures (8 to 13°C) without reduction of their quality (Tauber et al., 1993, 1997; López-Arroyo et al., 2000). Afterwards, depending on market demands and appropriate adjustment in the mass - rearing system, the immediate, predictable and synchronous completion of post - diapause development and commencement of egg laying by females could be feasible.

Another important aspect in the commercialization of chrysopid species and other natural enemies is the quality control of the individuals to be released. A first important step in the mass - rearing is the correct identification of the species to be reared, as well as the verification of it at various time periods after setting up the rearing. Chrysoperla sp. colonies are known to deteriorate after rearing for a long period of time under controlled laboratory conditions (Jones et al., 1978; Chang et al., 1996). Regular quality control inspections of the stock colony in terms of survival and reproduction performance combined with proper handling of chrysopids life - cycle (i.e., maintenance in diapause or at low temperatures) seems to be crucial for the successful marketing of chrysopids. A few studies have noted the need for setting up certain standards in the commercialization of chrysopids (Gardner and Giles, 1996; Daane and Yokota, 1997; O’Neil et al., 1998; Silvers et al., 2002).

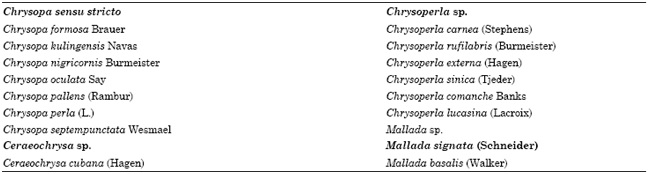

The efficiency of chrysopids as biological control agents against aphids was studied in 1742 for the first time (Senior and McEwen, 2001). Since then, the vast majority of published research articles concerning the evaluation of certain chrysopid species for use in biological control programs have been mainly focused on Chrysoperla species. These species are considered to be important biological control agents in certain agroecosystems worldwidely and they are the most commonly released commercially available chrysopids (Tauber et al., 2000). Besides Chrysoperla sp., there is also some scattered information concerning other important chrysopid species tested for use in biological control belonging to other genera, as well, such as Chrysopa, Mallada and Ceraeochrysa (Table 1).

Table 1: Some chrysopid species which have been studied for use in biological control under field or laboratory conditions*

*Reported by Ridgway and McMuphy (1984), Hagen et al. (1999), Albuquerque et al. (2001), Daane and Hagen (2001), Maisonneuve (2001), Senior and McEwen (2001)

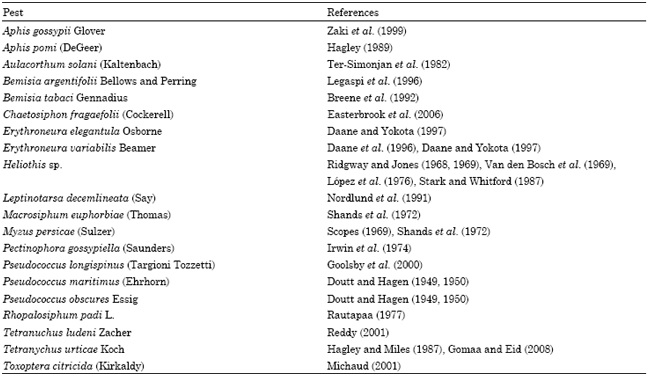

Table 2: Pest species which have been successfully controlled by Chrysoperla species

Chrysoperla species have been released to control aphids in pepper, eggplant pea, potato and cotton fields. They have also been used to control Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say) in eggplants, Panonychus ulmi (Koch) in apple orchards and Heliothis virescens (Fabricius) in cotton (Nordlund et al., 2001). In the greenhouse, C. carnea, Chrysopa septempunctata Wesmael, Chrysopa formosa Brauer and C. perla have been successfully used for aphid control in several crops, such as pepper, cucumber, eggplant, lettuce (Tulisalo, 1984). Chrysopids released in North America for biological control include mainly C. carnea to control several pests, such as mealybugs, aphids cicadellids and aphids, C. rufilabris to control chrysomelids, whiteflies, aphids and cicadellids, Chrysoperla externa (Hagen) against noctuids (Daane and Hagen, 2001) and Chrysoperla plorabunda (Fitsch) to control aphids (Michaud, 2001 and references therein). Some examples of the earliest till the latest attempts to use Chrysoperla species in biological control both in field crops as well as in greenhouses are shown in Table 2.

In the Neotropics, according to Albuquerque et al. (2001), C. externa and Ceraeochrysa species (e.g., Ceraeochrysa cubana (Hagen)) are considered to be of primary importance for the implementation of biological control programs.

In the Australian region among the very few indigenous lacewing species, M. signata is the most promising candidate for use in biological control (New, 2002), whereas in China Chrysoperla sinica (Tjeder) has already been used in augmentative release biological control programs with success (Senior and McEwen, 2001).

Many species of the genus Chrysoperla, such as C. carnea, C. rufilabris and C. externa are important biological control agents (Albuquerque et al., 1994; Legaspi et al., 1994). Among the above mentioned species, C. carnea is the most studied species that has also been extensively used in releases in the context of biological control. According to recent studies, C. carnea comprises a complex of species that is generally referred to as Chrysoperla carnea Stephens sensu lato (Thierry et al., 1992; Henry et al., 2001). C. carnea species is considered to be a mega - species referred to as - carnea - group, which is one of the four species groups of the genus Chrysoperla. Although there are morphological differences between the species of the other three groups (comans -, nyerima - and pudica - group), the species belonging to the carnea - group are morphologically uniform (Brooks, 1994).

According to several studies, C. carnea consists of many reproductively isolated species that have no morphological differences and produce courtship songs of low frequency by vibrating their abdomen on the substrate when they are ready to mate. The songs are produced both by females and males, they are a prerequisite for the mating and according to some researchers they are species - specific and could be considered as a reliable index of the species identity (Henry et al., 2001; Noh and Henry, 2010).

To date, the songs of four cryptic species recorded in North America (C. plorabunda, Chrysoperla adamsi Henry, Wells and Pupedis, Chrysoperla johnsoni Henry, Wells and Pupedis and Chrysoperla downesi (Banks) sensu stricto) (Henry, 1979b, 1993; Henry et al., 1993), six in Europe and Western Asia (Chrysoperla mediterranea Hölzel, Chrysoperla lucasina (Lacroix), C. carnea (Stephens), Chrysoperla pallida Henry, Brooks, Duelli and Johnson, Chrysoperla agilis Henry, Brooks, Duelli and Johnson, Chrysoperla zastrowi arabica) (Henry et al., 1996, 1999, 2002, 2003, 2006), one in Africa (Chrysoperla zastrowi zastrowi (Esben - Petersen)) (Henry et al., 2006) and two in Eastern Asia (Chrysoperla nipponensis (Okamoto) types A and B) (Henry et al., 2009) have been described in detail. The species C. plorabunda was confirmed to be a distinct species from C. carnea although it was considered to be its synonym for a long time (Henry, 1979a, 1983, 1985a, b; Henry and Wells, 1990; Henry et al., 1993). There is a small variation between these songs even for populations originating from regions thousands of kimometers away (Henry and Wells, 1990). However, Tauber et al. (2000) argue that the description of new species based only on their songs is not reliable, since there are not enough data concerning songs variation in different seasons and geographical areas or connecting distinct songs with different biological traits.

In any case, when considering the use of Chrysoperla species in biological control there is an urgent need for a correct identification of the species to be released. There is a speculation that since C. carnea has been considered as a single species for a long period of time, sibling species may have been introduced as biological control agents in areas where another species of the - carnea group predominated (Senior and McEwen, 2001). Due to the well documented variation between the chrysopid species in certain life trait characteristics such as habitat and prey preference, seasonal life cycles and tolerance to several abiotic environmental factors (e.g., temperature or relative humidity) (Tauber et al., 2000), such releases of the inappropriate sibling species could be considered at least to some extent, as the causal factor of the recorded failures in the attempt to use chrysopids in biological control through augmentation releases.

When considering the different biological control tactics used to control pests, four different methods could be used when releasing chrysopid species:

In general, chrysopids have not been widely used in classical biological control and most work has been focused on their augmentation and conservation in the agroecosystems (Hagen et al., 1999). The large numbers of different chrysopid species occurring worldwidely have rendered the importation of an exotic chrysopid species to another country, useless.

Augmentation of natural enemies by means of inoculative releases aims to the provisional pest control for a long period of time through the reproduction and establishment of the natural enemy in the crop. Due to the great ability of chrysopid adults to disperse and the occasional need of immediate response in pest control, augmentation of chrysopids by means of inundative releases (mainly based on the ability of the individuals released to suppress pest populations) has been most commonly used in cases where release cost is not restrictive. A few researchers have also documented the efficacy of chrysopids in augmentation biological control (Ridgway and Jones, 1969; Daane et al., 1996; Daane and Yokota, 1997; Ehler et al., 1997; Knutson and Tedders, 2002).

Conservation techniques in biological control aim to the establishment of increased numbers of a chrysopid species within the field through the enhancement and manipulation of their habitat (e.g., crop fields). Research related with chrysopids has been mainly focused on the evaluation of certain chemicals or blends that could be sprayed on plants and act as attractants for the chrysopids and on the use of food supplements, such as artificial honeydews or pollen (Tauber et al., 2000; Nentwig et al., 2002; James, 2003, 2006; Toth et al., 2006, 2009; Venzon et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2008). Other conservation methods that have application in the manipulation of chrysopids are the use of hibernation shelters for the protection of overwintering adults (McEwen and Sengonca, 2001; Wennemann, 2003; Weihrauch, 2008), cultural methods, such as intercropping (Senior and McEwen, 2001) or the use of flowering plants (Shrewsbury et al., 2004).

Chrysopids are most commonly released as eggs or larvae, but there are also cases that adults have been used in biological control. Eggs have been tested most extensively in relation to their application in the field (Tauber et al., 2000). The release of adults has been considered to be problematic, due to the fact that they usually disperse and leave the target field before ovipositing (Duelli, 1984). This problem might be confronted by releasing adults previously fed in the insectary during preoviposition period, so as to be ready to oviposit after release in the field (Nordlund et al., 2001).

Chrysopid eggs mixed with rice hulls or vermiculite, attached on oviposition substrates or destalked are usually dispersed manually to ensure their uniform distribution in the field. Solid mediums (e.g., rice hulls) as carrying agents of the eggs have the disadvantage of not offering a good retention on the plant in comparison with liquid mediums (e.g., agar solutions) that help eggs to be easily attached on the leaves (Tauber et al., 2000). Chrysopid larvae can be released manually by placing rearing units on the plant or with the help of a paintbrush. They are also formulated mixed with rice hulls inside bottles and applied on the plants (Nordlund et al., 2001).

Advances in release methods of chrysopid eggs include the development of mechanical devices by commercial companies that use low pressure air and a liquid medium for the distribution and efficient adherence of the eggs on the plants. Furthermore, aerial application by means of model airplanes or helicopters, have been tested for use in augmentative biological control with chrysopids. The mechanical application of chrysopid eggs and larvae has been the subject of several studies mainly in terms of the effects of automation on their viability (Nordlund et al., 2001 and references therein).

To date, the most important and commonly used commercially available chrysopids are Chrysoperla species. The species C. carnea, Chrysoperla comanche Banks and C. rufilabris are being mass - reared and commercially sold by many companies in North America since years. Furthermore, C. carnea, C. externa and C. sinica are commercially available in Europe, Latin America and Asia, respectively (Tauber et al., 2000; Nordlund et al., 2001).

Concerning the different stages that could be purchased by a grower, chrysopid eggs, larvae, cocoons and adults are all commercially available by several companies and in different formulations. Eggs and larvae, usually sold in thousands, are cheaper than cocoons and adults. The top seller of all available species is C. carnea although there is a lot of concern whether this is the true C. carnea or not. According to Tauber et al. (2000), the identification of the species of the Chrysoperla stock should be the first crucial step at the onset of the culture to be mass - reared.

Besides different chrysopid formulations, food supplements, attractants as well as hibernation boxes are also available commercially to be used in conservation biological control. Food supplements for adults include bottles or bags containing yeast or pollen and nectar substitutes that could be mixed with water and applied as a paste or sprayed on the plants. By enhancing the availability of food for chrysopid adults, the companies that provide these supplements claim the increase in oviposition of the adults, their maintenance in the target field and subsequent successful pest control. Eggs of Ephestia kuehniella Zeller, is a factitious food commonly used for mass - rearing chrysopids, as well as other predatory insects. It is commercially available as a supplementary food for predatory insects within the context of biological control. In the case of chrysopids, it could be used as supplementary larval diet. However, to our knowledge there are no studies related to the benefits of using E. kuehniella eggs on the population of chrysopids under field conditions. Hibernation boxes also known as ‘lacewing chambers’ and several attractants are currently commercially available.

The most efficient biological control agents of the genus Chrysoperla species share some common characteristics (presented below) that enhance their role in biological control, in relation to other chrysopid species.

Besides Chrysoperla species, all of the above characteristics have been recorded in species of other genera, such as Ceraeochrysa (López-Arroyo et al., 1999a, b; Albuquerque et al., 2001), Mallada (Daane, 2001; New, 2002) and Dichochrysa (Principi, 1956; Pappas et al., 2007, 2008a, c, 2009). Furthermore, the larvae of the above mentioned genera could be protected by ants and other natural enemies by carrying ‘trash’ on their dorsa (Principi, 1956; Eisner et al., 1978). Due to the common desirable characteristics of Dichochrysa, Mallada and Ceraeochrysa with Chrysoperla species and their abundance is several crops, they could be assumed to also play an important role in biological control (López-Arroyo et al., 1999a, b; Tauber et al., 2000; Daane, 2001).

Within C. carnea complex many species are included that are not sufficiently studied in terms of their performance in the field as biological control agents. Given the commercial success of C. carnea, there is an urgent need other species such as C. agilis, C. lucasina, C. mediterranea or C. pallida in Europe to be included in screening studies for efficient natural enemies. Furthermore, the biology of species of the carnea compex is poorly studied, although there is scattered data to suggest their considerable variation in their performance in different habitats and biotic or abiotic factors (Tauber et al., 2000).

In order to enhance the role of Chrysopidae in biological control, the importance of other species than Chrysoperla should be evaluated. Among chrysopid species, Chrysoperla sp. are almost the only ones which are well studied and commercially available for use in biological control. By contrast, there are limited data on the biology of species belonging to the genera Dichochrysa, Mallada and Ceraeochrysa which could be also used commercially for release in biological control programs. For example, from the 130 known Dichochrysa species, only the biology of D. prasina, has been extensively studied under laboratory conditions (Pappas et al., 2007, 2008a, b, c, 2009). It has been found that D. prasina has those desirable traits that could support its amenability for mass - rearing and future commercialization (Pappas et al., 2007, 2008a, b, c, 2009). This is also the case for Ceraeochrysa and Mallada species. Ceraeochrysa cubana is considered a promising biological control agent in the Neotropics (López-Arroyo et al., 1999a, b; Albuquerque et al., 2001). Mallada signata is the only chrysopid species that has gained attention as an important indigenous predator in Australia (Horne et al., 2001), while the role of other chrysopids has been neglected (New, 2002).

Feeding habits of chrysopid species intended to be used in biological control should also be studied. They are all considered to be polyphagous predators of several soft - bodied arthropods. However, prey quality seems to be crucial for the successful completion of their immature development and subsequent adult performance (Principi and Canard, 1984). Therefore, prey preference or prey specificity of candidate chrysopid species should be further studied in detail so as they could be exploited for the control of the most suitable pests.